Few questions are more important, yet few answers are more elusive than this: How can schools ensure the safety of students, teachers and staff?

In the post-Columbine/Sandy Hook/Marjorie Stoneman Douglas era, it’s a perplexing issue that every superintendent places at the top of the agenda today.

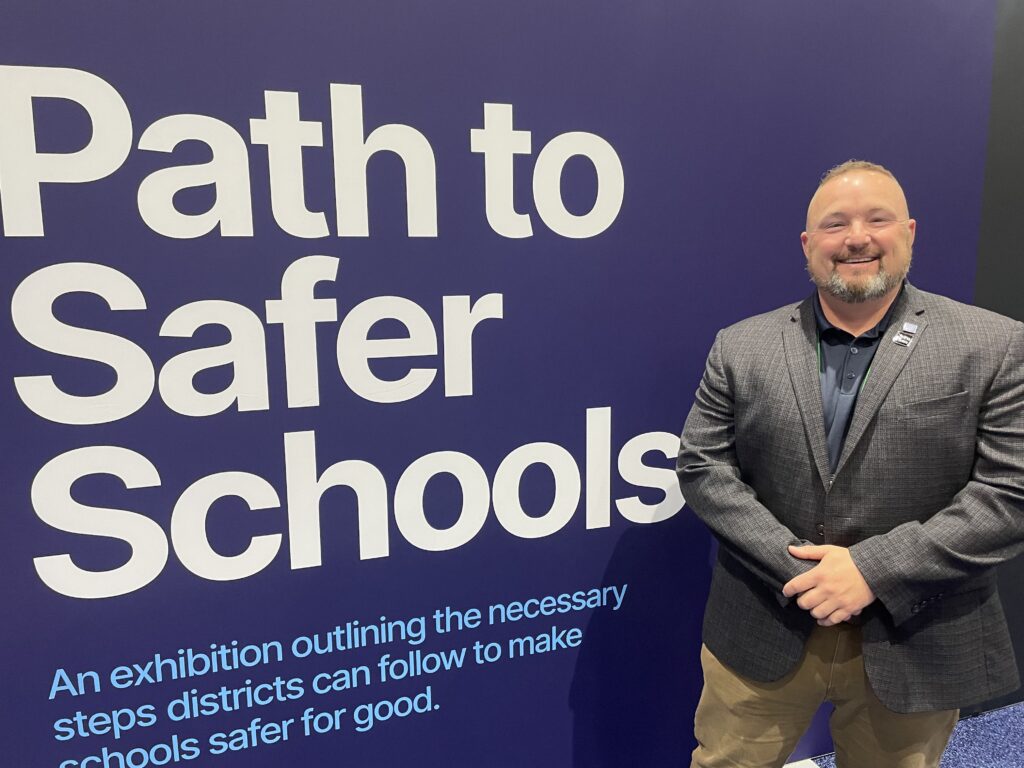

AASA’s 2024 national conference recognizes that priority with a major addition to the soldout exhibit hall: The convention’s walk-through School Safety and Security Learning Lab.

The lab, co-sponsored by AASA and ZeroNow, is actually a self-guided experience in which conference attendees walk through a booth with eight-foot-tall panels on both sides that explore a different aspect of school safety, including prevention, funding of safety and security programs and more.

Several safety and security companies had representatives stationed at the conclusion of the walkway to serve as informational resources.

“As much as we try, we can’t keep up,” said Sa Dao, director of business development for Kokomo24/7, whose software tracks school visitors and issues alerts during emergencies. “It’s overwhelming.”

Still, the hunt for solutions has enlisted scads of entrepreneurs with many of them demonstrating their wares at the 2024 AASA conference.

Michael Day, co-founder of Safe EVAC, said he was devastated when two school shootings occurred in Kentucky and Florida within a three-week period in 2018. “Right after that, I couldn’t shake it,” he said. “I knew technology was the answer.”

His company markets electronic signs whose color-coded messages alert students and staff to emergencies and direct them to safety.

Centegix, also present at the safety lab, markets a wearable badge that, when pressed, alerts a customizable list of responders – everyone from school nurses to local police – that an emergency is unfolding.

“It’s a powerful tool you are giving everybody in the building,” said G. Elgin Card, superintendent of Cincinnati’s Princeton City School District, which adopted the system last fall. “This is a way to give people peace of mind.”

Another exhibitor, Armoured One, sells a reinforced film that is applied to tempered glass windows, making them virtually shatterproof. “We’re not trying to stop anything,” Armoured One’s Emma Henderson said. “We’re just trying to buy time.”

Stopping all these tragedies, though, is the mission of Zero Now, a nonprofit think tank.

“You can’t get there if you don’t have a goal,” said Jason Stoddard, a Zero Now member and director of safety and security for Charles County Public Schools in Maryland.

A complex problem, school safety lacks a tidy, uniform, one-size-fits-all answer. Stoddard, an Air Force veteran and former police officer, rejects the notion that schools should become “hard targets,” locked-down fortresses patrolled by armed guards.

“We can park a tank on the roof,” Stoddard said. “It’s not going to stop things from happening.”

Instead, many of those present at AASA’s event suggested, start by answering another key question: Who owns school safety?

The School Safety and Security Learning Lab’s messaging begins by urging educators to appoint a security team. Among this group’s responsibilities: assess vulnerabilities; find grants to fund safety programs; create a positive school climate; and respond to threats quickly and confidently.

One more important message: Drop the my-way-or-the-highway attitude, Stoddard said. Collaborate with staff, students and community members.

“School safety,” he said, “is a team sport.”

(Peter Rowe is a reporter for Conference Daily Online and a freelance writer in San Diego.)