By Amanda Paule |

As an educator and former principal engaged in antiracist work, the last place Sarah Fiarman expected to find racism was within herself.

But during a course she was teaching at Harvard, Fiarman started noticing some of her Black students having side conversations during class. She asked her colleague Tracey Benson, an assistant professor of educational leadership at UNC-Charlotte, for advice on how to address the problem respectfully. Should she pull the students aside and speak to them that way? Benson’s response surprised her.

“Sarah, I guarantee you that if you go to your next class and watch the white students, you will see some white students doing exactly the same thing,” she recalls Benson saying.

Fiarman felt immediately defensive, but she trusted and followed her colleague’s advice. She was surprised to learn that Benson was right: Her white students were having the same side conversations she had previously attributed only to her Black students, but she had been interpreting the behavior differently based on race.

The experience enlightened her to the prevalence of unconscious racial bias and its negative impact on students. Fiarman later joined Benson to coauthor the book Unconscious Bias in Schools, which they discussed during an AASA national conference session by the same name on Friday, Feb. 19.

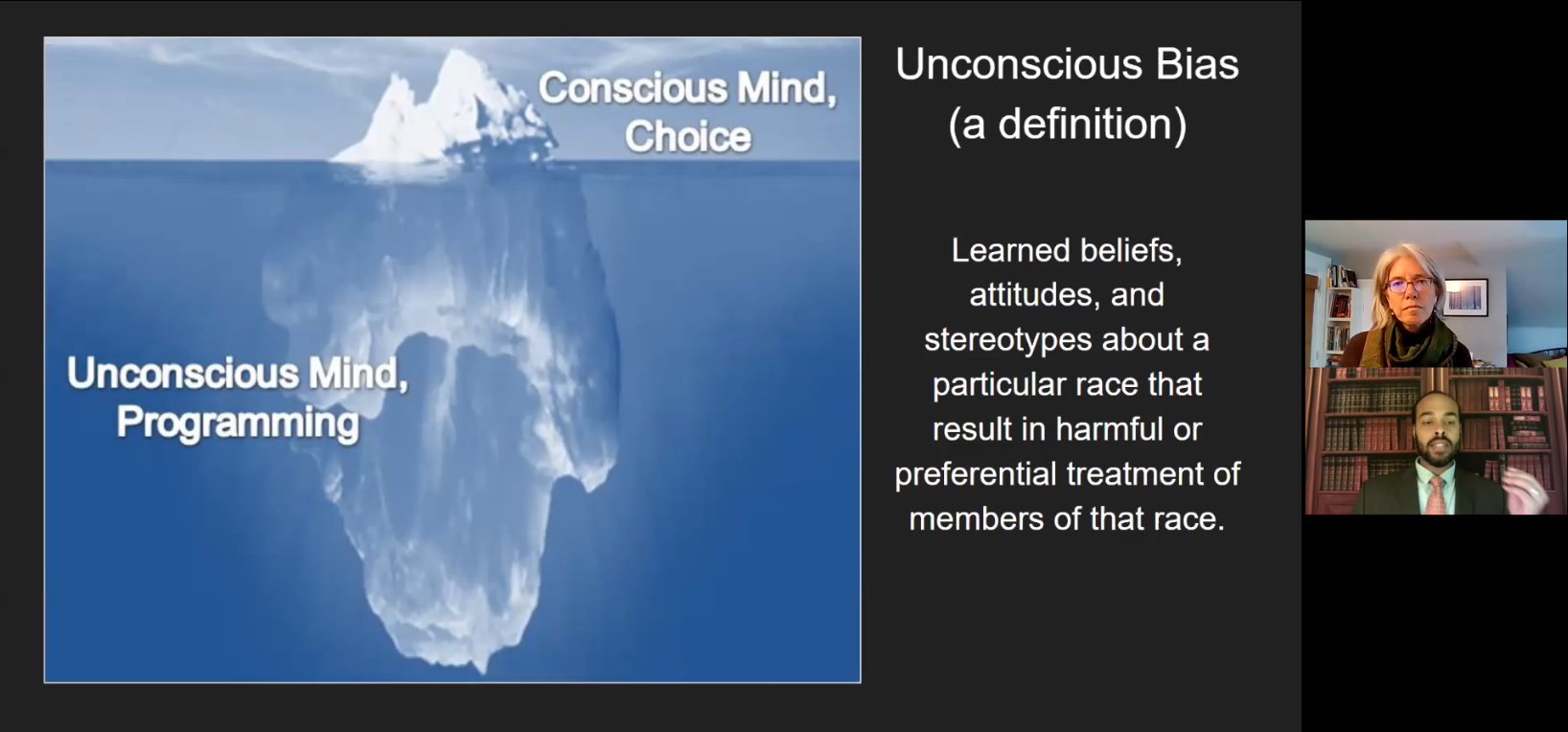

“A lot of us want to be seen as good, non-racist people in our conscious mind. We don’t have any conscious access to the way our racism shows up,” Benson said during the session. “But below the surface is a large swath in the unconscious mind, the unconscious programming of growing up in a society where we do not consciously ingest racism, but it lives in our unconscious mind.”

This unconscious programming comes from a variety of sources, including social circles, movies and TV, news, advertising and even systems like the greeting card aisle at stores that segregate cards with non-white figures into a separate section.

This unconscious programming comes from a variety of sources, including social circles, movies and TV, news, advertising and even systems like the greeting card aisle at stores that segregate cards with non-white figures into a separate section.

Research has shown the consequences of unconscious bias across sectors from medicine to hiring to policing, the presenters said. In education, one study showed that when given the same poorly written essay, teachers were more likely to offer feedback for improvement when they thought the writer was a white student than when they thought the writer was a student of color.

“The research is very clear that it’s not possible for us to be free of unconscious biases,” Fiarman said. “We are all absorbing these biases. We can’t choose to be exempt from this.”

In their book, Benson and Fiarman seek to give educators a better understanding of unconscious racial bias and how it shows up in themselves and their schools. They also provide resources for starting and maintaining anti-racist conversations and practices in schools.

“Teaching people about unconscious racial bias helps educators focus on their impact, without getting all defensive about intentions and shutting conversations down,” Fiarman said.

Benson also founded the Anti-Racist Leadership Institute, a monthly program he designed to guide and empower school leaders in implementing racial equity initiatives in their own districts.

Video: Authors Share Practical Measures on Combating Unconscious Bias in Schools [4:18]

(Amanda Paule is a junior magazine, news and digital journalism major at Syracuse University’s Newhouse School of Public Communications and an intern with AASA’s Conference Daily Online.)