A throng of school superintendents from around the country packed a session room Thursday morning for “The Politics of the Superintendency: An Emerging Framework” that was one part panel discussion and one part group therapy.

As the seats filled and audience members took to standing in the back of the room, one attendee leaned over to his neighbor and shared a knowing glance. “I thought this might be well-attended,” he said with a laugh.

If you’re up on the news or serving in a public school leadership role during the past few years, you’ll surely know why.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, school boards in various communities across the country have come under the control of conservative “parents’ rights” activists, with board meetings becoming emotionally contentious battlegrounds for culture war battles around diversity, race and racial history, books in school libraries and LGBTQ issues.

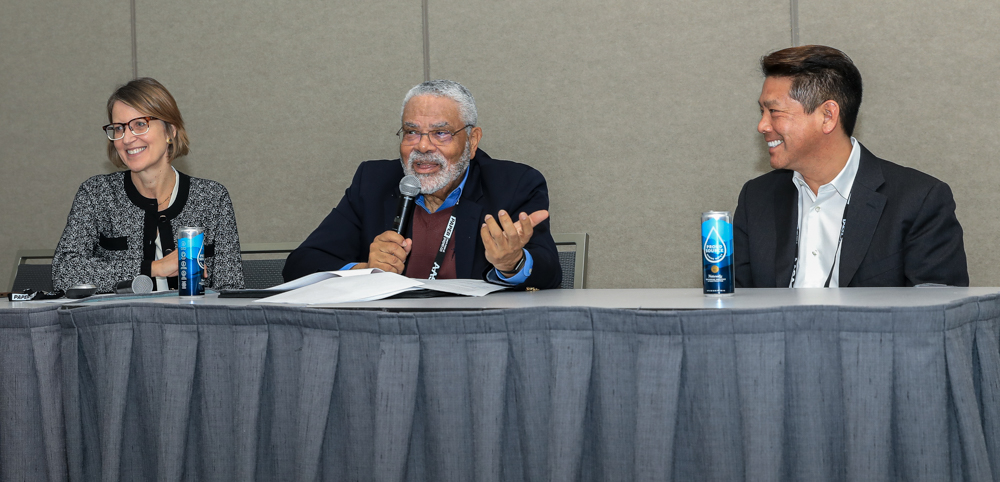

The discussion was led by Jennifer Cheatham, senior lecturer at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and co-chair of the Public Education Leadership Project. Panelists included Carl Cohn, professor emeritus and senior research fellow at Claremont Graduate University and former superintendent of Long Beach Unified School District, and David Miyashiro, superintendent of Cajon Valley Union School District in nearby El Cajon, Calif.

Cheatham and Cohn have partnered to create the Collaborative on Political Leadership in the Superintendency, which aims to equip public school district superintendents to effectively navigate the current politics impacting K-12 education.

Their message? In a new landscape where all politics is now national, local superintendents must hone their political leadership skills to make a positive difference academically and in other ways for their students.

To kick off the event, Cheatham asked the assembled educational leaders to rate how they feel about navigating politics in their community. By show of hands, the largest group of respondents saw it as a “necessary evil.”

“When I got into this business, it wasn’t about politics, it was about students,” one attendee responded. “Unfortunately, since COVID, it has become a political battlefield.”

Cohn, who became superintendent in Long Beach against the backdrop of the 1992 riots in Los Angeles, spoke to his decision early on in his career to “practice policy to truly rescue kids.” During his decade in the role, he endorsed and supported school board candidates, a form of political engagement he credits for bringing three decades of stability and continuity to the large district.

As he travels around Southern California, he’s seen the new dynamic at play.

“I go to these raucous school board meetings,” Cohn said. “I remember seeing this trans girl sitting in the same row, and at one point she went up to the podium and spoke. She looked at the school board and said, ‘I just want to feel safe in school.’ That really captured the moment in this five-hour back and forth with all these scary characters coming out. … That’s what we need to ensure for our students.”

Miyashiro spoke about his experiences leading a district that became the first California school system to re-open at scale during the pandemic in 2020 — a decision he made to support families where the parents were essential workers without access to childcare, but one that generated considerable statewide blowback.

Launched in 2023, the Collaborative on Political Leadership in the Superintendency conducts research to identify the knowledge, skills and dispositions superintendents need to navigate the political waters described by Cohn and Miyashiro.

The resulting framework emphasizes skills such as political mapping of the community you serve and engaging with that community to develop and mobilize around a shared vision. Another key is relationship building, particularly across the lines of ideological division. Cheatham, who formerly worked as superintendent in Madison, Wis., also spoke to the importance of creating safe spaces for superintendents to connect with one another about leadership and problems of practice.

“We can’t just be in our isolated bubbles anymore,” she said.

(Michael Klitzing, a freelance writer based in San Diego, is a reporter for Conference Daily Online.)